Now that I’m working as the City of Omaha’s Streetcar Operations Manager, a role where I will oversee the implementation of streetcar service for the Omaha Streetcar Authority, the focus of my Grow Omaha column will change. I’ll focus on news and information about Omaha’s rail and help readers understand how streetcars have impacted other cities and regions – along with ours – as we get closer to opening in 2028.

This month, I’m sharing stories from a visit I took to the Pacific Northwest earlier this year, when I rode streetcars in Tacoma, Seattle and Portland. We can learn a lot by studying successful transit in other cities as we plan Omaha’s streetcar project. How have other cities approached extensions? How long does building an extension take? What neighborhoods do they serve and what are the impacts to development and transit ridership? Let’s take a closer look.

There are 21 U.S. cities with streetcar systems (there are more if you count cities that have converted their streetcar systems to light rail or light rail systems that have a more streetcar-like component in an urban area like a downtown). Of those 21 cities, 15 have modern vehicles similar to Omaha’s future system. Several cities have plans, or have discussed extending, their streetcar. Six cities have built notable extensions:

- Little Rock, Arkansas — Metro Streetcar: 2.5-mile starter line opened in 2004, 0.9-mile extension opened in 2007.

- Milwaukee, Wisconsin — The Hop: 2.1-mile starter line opened in 2018, 0.4-mile extension opened in 2024.

- New Orleans, Louisiana — New Orleans Regional Transit Authority: Streetcar service started in 1893 and has been continuously running on the St. Charles Line, currently a 6-mile line. The 2-mile Riverfront Line opened in 1988 and reopened in 2025 after a closure that started in 2018. The 5.5-mile Canal Street Line opened in 2004. The 2.4-mile Rampart-Loyola Line opened in 2013 and reopened in 2024-2025 after closing in 2019.

- Portland, Oregon — Portland Streetcar: 2.4-mile starter line opened in 2001, extensions to 8.5 miles that opened in different phases including 2005, 2006, 2007, 2012, and 2015.

- Seattle, Washington — Seattle Streetcar: 1.3-mile South Lake Union Line opened in 2007 with the 2.5-mile First Hill Line opening in 2016.

- Tacoma, Washington — T Line: 1.6-mile starter line opened in 2003, 2.4-mile extension opened in 2023.

Of those cities, Portland, Seattle and Tacoma have implemented considerable extensions, while Little Rock and Milwaukee’s extensions were included in their streetcar systems’ initial design concepts. New Orleans is a special case because of its large system and long history. Note that Kansas City was not included in this list, as its north and south extensions have not opened yet, although they should be in operation by the end of this year.

Let’s focus on the Pacific Northwest extensions, which are each very unique and offer different lessons for Omaha. I visited each of these systems earlier this year while attending a conference in Portland.

Tacoma

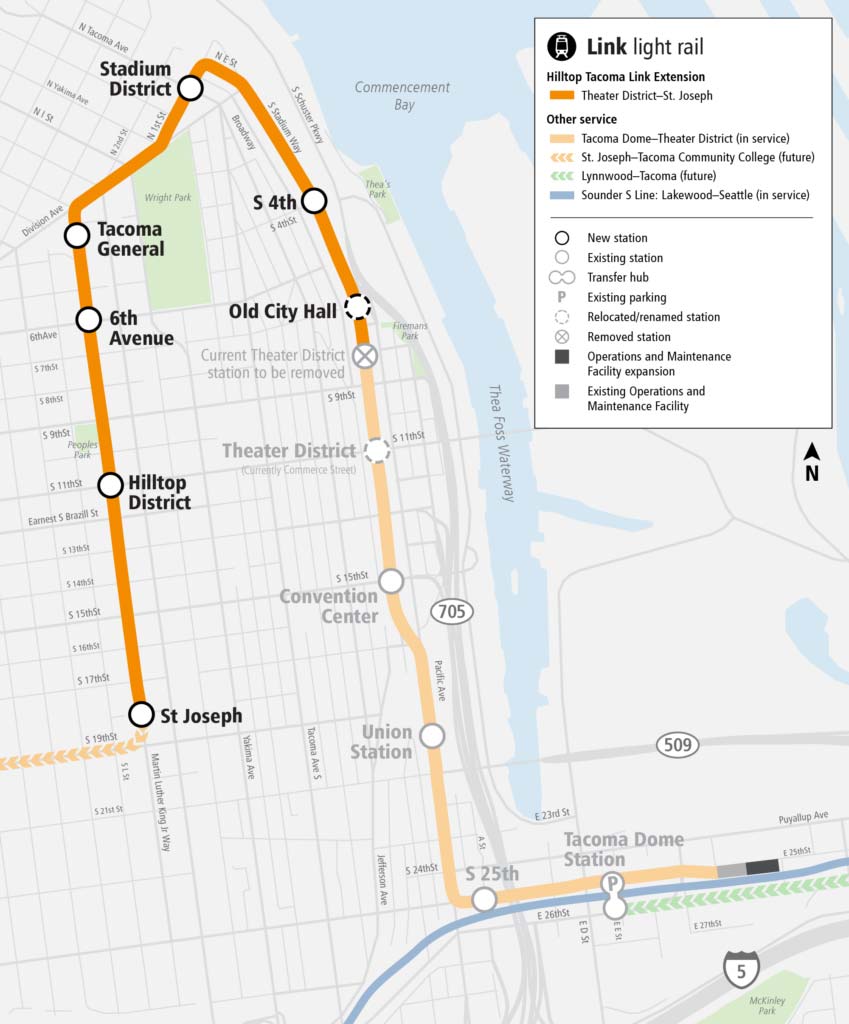

Map of the Sound Transit T Line, or Tacoma Link, showing the Hilltop extension

My first stop was Tacoma, Washington, which is easily accessible from the SEA-TAC airport by the Sound Transit express bus (the commuter rail has very limited hours). I first visited this line in 2004, one year after it opened, and was excited to see the extension that opened 20 years after the first line.

The Tacoma Link is technically considered a light rail line as it fits within the Sound Transit light rail system. Tacoma was built to “light rail standards,” meaning that the track bed is built deeper and the infrastructure is designed to handle the slightly heavier light rail vehicles. The ultimate plan is to have the 1 Line light rail extend south to Tacoma – also note that there is parallel commuter rail and express bus service that will likely continue to exist.

On board the T Line

Tacoma’s first streetcar extension took time to get into construction as the city had initial plans for either a robust streetcar network (proposed in 2007) or eventually being the south end of a light rail extension. A “Sound Transit 3” measure passed by voters in 2016 secured funding for the extension to Hilltop, the first phase to bring the streetcar to the Tacoma Community College. The light rail extension to Tacoma is planned to open in 2035, while the Tacoma Community College Hilltop extension has an anticipated opening in 2039.

The final stop on the new Tacoma extension

The Tacoma Link initially operated at a zero-fare, but when the Hilltop Extension opened, it joined the rest of the Sound Transit system in charging a fare. Daily ridership is at about 4,000 passengers, and the extension has been responsible for new development in the Hilltop neighborhood and the Stadium District, including several multi-family buildings.

Seattle

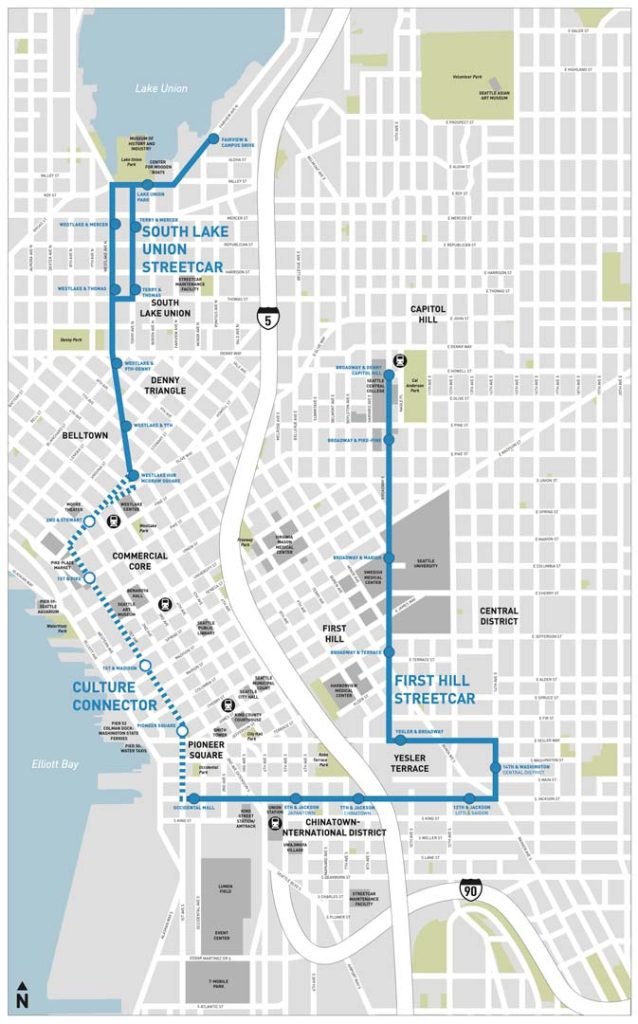

Map of the Seattle Streetcar system

Seattle is a tale of two very different streetcar lines. My last visit to Seattle was about 13 years ago, and I checked out the initial South Lake Union line that opened in 2007. The First Hill line opened in 2016 and has slightly later operating hours, so I rode that in the late evening and was very impressed at how full the cars were.

Passengers waiting to board the streetcar on the First Hill line

The South Lake Union line was part of a neighborhood redevelopment that was supported by a business community group led by some of the larger property owners and institutions that supported the project. Many improvements to the original line were made since the initial opening, including the addition of light rail service at the Westlake Station in 2009. Transit signal priority was added at some intersections in 2011, an additional streetcar was added to the fleet in 2015 to increase the service frequency, and transit-only lanes were added to some segments in 2016, all which made the streetcar service faster and more reliable.

The First Hill line was envisioned as both an extension of the South Lake Union line (through central downtown) and an alternative to building a more expensive light rail extension from the International District/Chinatown Station. Ultimately, the extension was cut short to this light rail station and not physically connected to the South Lake Union line. The First Hill extension project was funded by the “Sound Transit 2” program. Similar to the South Lake Union line, the First Hill line added transit signal priority and transit exclusive lane improvements after opening in 2018.

The First Hill line has a daily average of more than 3,500 passengers, while the South Lake Union line has a daily average of just under 1,000 passengers. The First Hill line is about twice as long as the South Lake Union line, so First Hill has almost twice as much ridership by distance, which was easily noticeable during my rides on each line. The First Hill line has had some impact to development, but not nearly as much as the South Lake Union line. Conversely, the Frist Hill line has had better ridership results by serving an already dense and walkable transit corridor.

South Lake Union terminal at Westlake with new development in the background

There are further extensions planned in Seattle. A proposal that nearly started construction is to connect the two separate lines with the Culture Connector (formerly Center City Connector). This extension would serve popular downtown destinations just west of the light rail stations and would increase mobility through downtown while also increasing ridership throughout the entire system. Other extension plans include a half-mile extension of the First Hill line north along Broadway and northwest and northeast extensions of the South Lake Union line.

Portland

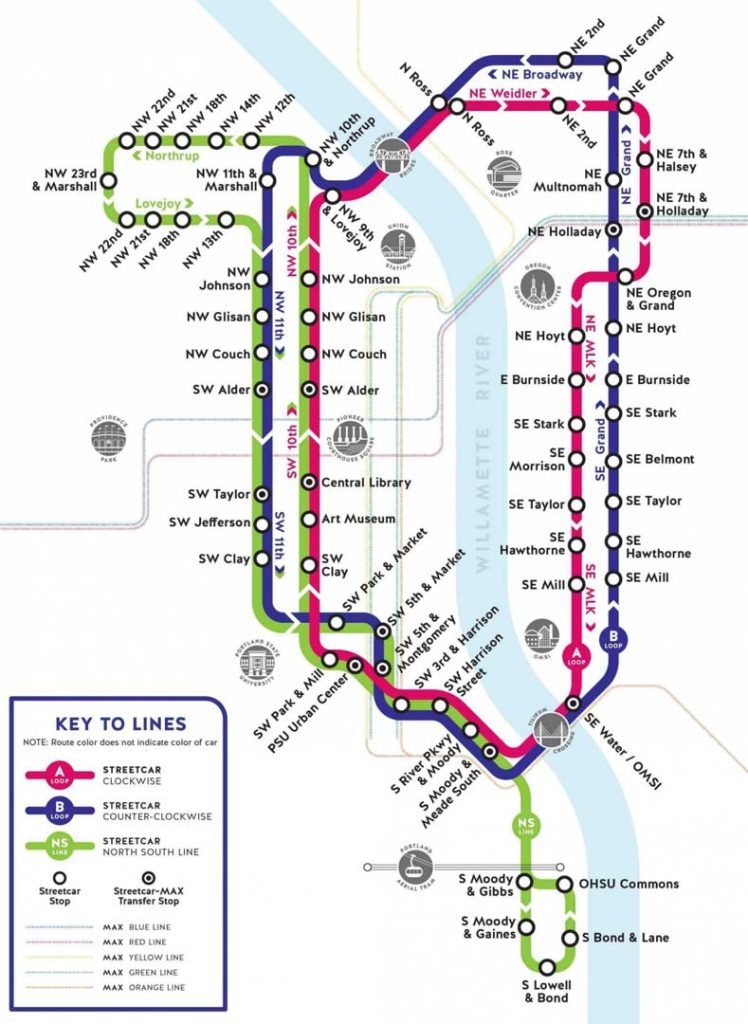

Map of the Portland Streetcar system

Portland, Oregon, is the birthplace of the modern streetcar movement in the United States. It was part of a transit pilgrimage that I took in 2004 as I was starting grad school, and I have been fortunate to travel back to Portland several times over the years for business. I rode Portland’s extensions on previous visits, so this time, I was focused on riding the streetcar more for its intended purpose — local urban trips. My favorite restaurant in Portland is the original Old Spaghetti Factory and the Portland Streetcar North-South Line (which includes the original line) nearly drops you off at the doorstep. I also like visiting Powell Books (an early streetcar opponent-turned-supporter).

Portland Streetcar on the original alignment

Portland has taken different approaches with its streetcar extensions over the years and now boasts the most extensive “new” or second-generation streetcar system in the United States. Starting with the original Central City Streetcar project that opened in 2001, Portland’s initial extension strategy was to continue with small, incremental additions. The first three extensions were each about a half-mile long, to the southeast of the original line, and opened in 2005, 2006 and 2007. These extensions created the 4.1-mile North-South line that exists today.

The next extension was much larger and would nearly double the size of the Portland Streetcar alignment. This is known as the Central Loop line, and planning started in 2003 with the Eastside Streetcar Alignment Study, which proposed using the Broadway Bridge to the north to cross the Willamette River and multiple options for crossing the river to the south, which included a possible new transit and pedestrian bridge. The extension used the first streetcars built in the United States, by United Streetcar, a subsidiary of Oregon Ironworks. The two phases of the extension opened in 2012 and 2015, culminating with the opening of the pedestrian- and transit-only Tilikum Crossing Bridge.

Just like the original line and extensions, the Central Loop line was responsible for spurring multiple new developments, this time on the east side of Portland. Total systemwide ridership peaked at about 16,000 per day before COVID and is now up to over 10,000 passengers on average per day. Similar to Seattle, Portland embarked on a program to increase the priority of the streetcar (and buses) at key traffic intersections and adding some streetcar-only lanes. Portland also permanently closed three stations to help improve travel times in 2016. These stations were converted to bikeshare stations.

Portland is studying extensions to the northwest to Montgomery Park and to the east to the Hollywood neighborhood. The Montgomery Park extension is planned to start construction by 2027.

What this means for Omaha

Each extension has useful lessons for Omaha’s first streetcar line and any potential extensions. There are some ideas that we can take advantage of now and in the future. A common theme with each streetcar system is to have an extension plan that is well thought out in terms of fitting the community, being properly organized and having a funding plan in place.

The City of Omaha received a $300,000 federal grant to study a potential streetcar line extension into north Omaha. Extensions to other parts of the city and region are also being discussed.

An approach that has worked well in Portland is to build extensions incrementally. Examples of this would be getting closer to the UNMC campus to the west and extending the line further north on 10th Street closer to the CHI Center and Charles Schwab Field. These short extensions were part of the original streetcar plan and were put on hold to consider how they would better fit with new development in these areas. Further extensions will require additional design and funding studies as well as additional coordination with Metro.

Another common theme among all the systems is to use extensions to improve travel time and reliability by incorporating transit signal priority at key street intersections along the route. This is something that we are planning to implement with the first line so that it runs smoothly from the start.

Finally, it is important to have a solid plan in place, which helps identify and prioritize the right extension(s) with which to move forward. This could be a next step for Omaha, as streetcar extensions can range from a few years to a couple of decades to open, so starting with a comprehensive plan may be best.